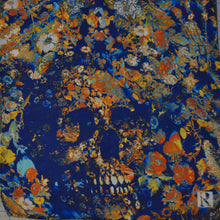

Skulls have a high degree of symbolism often used in art to represent death and change. Paul's design "Skullflowers" represents change (skull) and renewal (flower blossoms).

One of the best-known examples of skull symbolism occurs in Shakespeare's Hamlet, where the title character recognizes the skull of an old friend: "Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio; a fellow of infinite jest. . ." Hamlet is inspired to utter a bitter soliloquy of despair and rough ironic humor.

Compare Hamlet's words "Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft" to Talmudic sources: "...Rabi Ishmael [the High Priest]... put [the severed head of a martyr] in his lap... and cried: oh sacred mouth!...who buried you in ashes...!". The skull was a symbol of melancholy for Shakespeare's contemporaries.

Venetian painters of the 16th century elaborated moral allegories for their patrons, and memento mori was a common theme. The theme carried by an inscription on a rustic tomb, "Et in Arcadia ego"—"I too [am] in Arcadia", if it is Death that is speaking—is made famous by two paintings by Nicholas Poussin, but the motto made its pictorial debut in Guercino's version, 1618-22 (in the Galleria Barberini, Rome): in it, two awestruck young shepherds come upon an inscribed plinth, in which the inscription ET IN ARCADIA EGO gains force from the prominent presence of a wormy skull in the foreground.

The skull becomes an icon itself when its painted representation becomes a substitute for the real thing. Simon Schama chronicled the ambivalence of the Dutch to their own worldly success during the Dutch Golden Age of the first half of the 17th century in The Embarrassment of Riches. The possibly frivolous and merely decorative nature of the still life genre was avoided by Pieter Claesz in his "Vanitas", opened case-watch, overturned emptied wineglasses, snuffed candle, book: "Lo, the wine of life runs out, the spirit is snuffed, oh Man, for all your learning, time yet runs on: Vanity!" The visual cues of the hurry and violence of life are contrasted with eternity in this somber, still and utterly silent painting.

When the skull appears in Nazi SS insignia, the death's-head (Totenkopf) represents loyalty unto death. However, when tattooed on the forearm its apotropaic power helps an outlaw biker cheat death.

When a skull was worn as a trophy on the belt of the Lombard king Alboin, it was a constant grim triumph over his old enemy, and he drank from it. In the same way a skull is a warning when it decorates the palisade of a city, or deteriorates on a pike at a Traitor's Gate. The Skull Tower, with the embedded skulls of Serbian rebels, was built in 1809 on the highway near Niš, Serbia, as a stark political warning

Similarly, a skull might be seen crowned by a chaplet of dried roses, a "Carpe diem", though rarely as bedecked as Mexican printmaker José Guadalupe Posada's Catrina. In Mesoamerican architecture, stacks of skulls (real or sculpted) represented the result of human sacrifices. The skull speaks in the catacombs of the Capuchin brothers beneath the church of Santa Maria della Concezione in Rome, where disassembled bones and teeth and skulls of the departed Capuchins have been rearranged to form a rich Baroque architecture of the human condition, in a series of anterooms and subterranean chapels with the inscription, set in bones:

Noi eravamo quello che voi siete, e quello che noi siamo voi sarete."We were what you are; and what we are, you will be."

In Vajrayana Buddhist iconography, skull symbolism is often used in depictions of wrathful deities and of dakinis.